IN-DEPTH | The sound of one bitcoin: Tangibility, scarcity, and a "hard-money" checklist

/The first purpose of a scientific terminology is to facilitate the analysis of the problems involved.

—Ludwig von Mises on the role of monetary terminology

IMPORTANT UPDATE: What follows has been substantially updated, revised, and republished in other versions. The final version appeared in The Journal of Prices and Markets as, “Commodity, scarcity, and monetary value theory in light of bitcoin” (accepted 20 Oct 2014; published 24 Feb 2015; HTML, PDF). The arguments are substantively similar, but whereas the final version is more refined and academic in tone, the following was an initial overview treatment.

* * *

Tradable bitcoin units viewed as discrete objects of human action appear to be a new type of phenomenon, unprecedented. At times, they even appear to elude trusted monetary classification schemes. If such typologies were sound, however, they should not require correction so much as some careful revisiting within a new context of knowledge.

In this second installment on Bitcoin theory (following “Bitcoins, the regression theorem, and that curious but unthreatening empirical world” (27 February 2013), we seek to further clarify the economic nature of Bitcoin by closely reexamining the concepts of scarcity, goods, and tangibility. We distinguish what we will label economic-theory and property-theory senses of the word “scarcity” and attempt to more clearly differentiate scarcity from tangibility. This distinction helps overcome difficulties that have arisen in considering Bitcoin in relation to the monetary classification scheme pioneered in Ludwig von Mises’s The Theory of Money and Credit (TMC; original German 1912).

With these proposed building blocks in place, we examine bitcoin units viewed as scarce objects of human action using a typical set of criteria for explaining the historical-evolutionary strengths of metallic coins as media of exchange. How do tradable bitcoin units stack up directly on a list of “hard-money” criteria?

We also stress that the economic analysis of empirical cases must always be comparative. States of perfection, while useful in the advancement of pure theory, cannot legitimately be smuggled in to represent real empirical possibilities and serve as standards for comparison. How something compares to an imaginary state of perfection may help the theorist reason, but it is no cause to reject or prefer any real empirical option, which, whatever it may be, can never compete with any unrealizable, imaginary state.

The focus this time remains on the perspective of individual actors and discrete objects involved in action (which includes both tangible and intangible “objects”), with a central focus on economic theory. Planned future installments will then shift toward more system-level, market-level, and legal-theory perspectives. This step-by-step procedure reflects one aspect of an integral approach to the interplay of individual and system perspectives, as well as the parallel use of multiple, discrete fields, to enhance the totality of understanding.

Part I: Money Unveiled

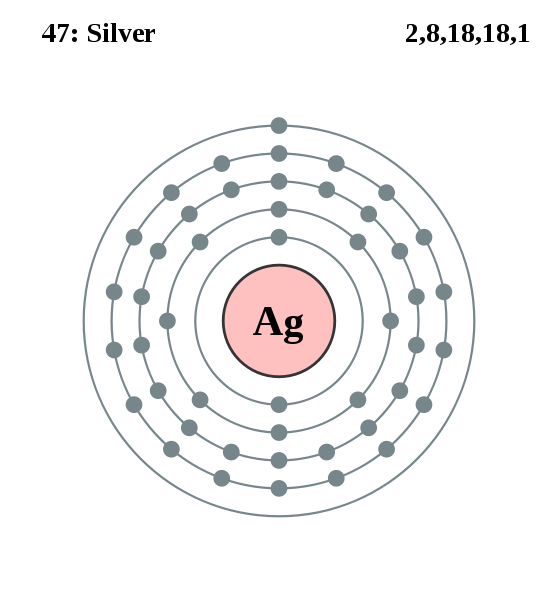

“I can pay you in eggs or a bunch of these specially configured nested electron-shell wrapped neutron/proton bundles. Your choice, buddy.” Image source: Pumbaa (original work by Greg Robson), Wikimedia Commons.

The thing is…

In taking a strictly subjectivist position on the nature of goods, the fact that bitcoin units might be described as “merely” the current status of accounting entries in the ubiquitously duplicated block chain (and therefore not “really” goods at all in themselves), poses less of a difficulty than it might at first appear to. Of interest for action-based economic theory is the observation that large numbers of market actors on a global scale are nevertheless treating these units as a type of scarce economic good in general and as a medium of exchange in particular. By way of illustration, quipping that silver is “really” just one particular and generally pointless arrangement of sub-atomic particles is of no avail for praxeology, which is based on a strict dualist distinction between teleological concepts and the more objective, causal concepts of the natural sciences.

If no existing category or “box” on a given monetary classification proved sufficient to contain Bitcoin, a new category might have to be appended. In investigating a new case, terms and categories should facilitate understanding rather than hinder it. In developing his terminology in Chapter 3, “The Various Kinds of Money,” in TMC (pp. 50–67), Mises sought to employ terms that would specifically facilitate economic analysis more effectively than the conventional and positive-law terms of the time (pp. 59–60). He notes on pp. 61–62 that:

Our terminology should prove more useful than that which is generally employed. It should express more clearly the peculiarities of the processes by which the different types of money are valued. [it should also help to overcome] the naive and confused popular conception of value that sees in the precious metals something “intrinsically” valuable and in paper credit money something necessarily anomalous. Scientifically, this terminology is perfectly useless and a source of endless misunderstanding and misrepresentation.

I do not believe that Mises’s classification scheme from TMC requires any fundamental revision to account for Bitcoin. We may only need to take a further step in the direction of a strictly dualistic action theory. This is the same direction of travel that gave rise to those classifications in the first place as Mises began to carry economic theory step by step further away from its objectivized past and toward its action-based future. Mises warned sternly in 1912 (p. 62) that:

The greatest mistake that can be made in economic investigation is to fix attention on mere appearances, and so to fail to perceive the fundamental difference between things whose externals alone are similar, or to discriminate between fundamentally similar things whose externals alone are different.

A fresh mystery from Vienna

Stephansdom in Vienna. Photo by Konrad S. Graf.

Among its many other contributions, Peter Šurda’s 2012 thesis, “Economics of Bitcoin: Is Bitcoin an alternative to fiat currencies and gold?” [90-page PDF; Vienna University of Economics and Business) carefully examined Bitcoin in terms of Mises’s monetary classification scheme from TMC. Up to a certain point, Šurda interpreted the situation in largely the same way as I have.

In a procedure reminiscent of the 1939 Agatha Christie novel And Then There Were None, he rejected, correctly I believe, one candidate after another as a place for Bitcoin within the TMC scheme (pp. 23–28). It is not any kind of money substitute (Bitcoin is not “redeemable” for any more fundamental unit). Even within Mises’s “money in the narrower sense” (senses other than money substitutes), Bitcoin is not credit money (no creditor/debtor relationship exists) and not fiat money (it lacks any legal-tender status or any other state-sponsored privileges, stamps, or certifications whatsoever to “prop it up”).

Somewhat disquietingly perhaps, Šurda and I had each arrived independently at just one final suspect. The only candidate that is even a remote possibility is: “commodity money.”

Yet surely this could not be quite right either. At this point, one might think it would have been easier to start by rejecting commodity money, and then try to make an analogy to some of the other categories. Commentators have tried to do this variously with fiat money and token money, for example. However, I do not think such claims hold up to scrutiny.

It is certainly quite odd in this context to begin trying to imagine Bitcoin as a “commodity.” True, in certain other contexts, “commodities” can have a quite broad meaning. In its broadest theoretical usage in purchasing-power theory, “commodities” are sometimes the euphemistic label for everything that is not money—all that against which money prices are paid. Nevertheless, for the most part, and certainly in this context, “commodity” takes its narrower and much more common meaning. It is a fungible physical material or product, such as metal, oil, grain, or these days interchangeable “commodity” memory chips or other general-purpose electronic components.

The opposite perspective: Vienna from high above in Stephansdom. Photo by Konrad S. Graf.

In the face of this apparent impasse, Šurda’s thesis next proposed several considerations. First, since he had already argued that Bitcoin is not a “money” (yet), but a secondary medium of exchange (p. 22), it need not necessarily fit on a chart of “money” in any case. Yet he also recognized that to some degree this just kicks the can down the road a few more yards. What if Bitcoin did somehow grow to eventually qualify as “money,” even by his own chosen definition? To this he proposed some alternative terminology from several existing sources (p. 26), such as “quasi-commodity money.”

He offers additional detail on this issue is in his recent post, “The classification and future of Bitcoin” (12 March 2013), where he notes perhaps the most important point of all:

The issue…is not some abstract classification for its own sake. The purpose of the classification system provided by Mises is to assist in the economic analysis of trade, money supply, price building, liquidity and so on. From this perspective, if we insist that we must keep the number of categories the same that Mises used, the economically closest category of Bitcoin would be commodity money.

I think further clarification may still be possible from some different directions. I suggested in the previous installment of this series that substituting the more subjectivist word “good” for “commodity” may already be a useful step, at least from a meaning-content point of view. This time, we venture further into language and context.

As always, meaning must come first; words have to follow along as best they can. Concepts are one thing; the words used to signify them another. To me these are not just theoretical claims, but my lived experience working as a professional translator for many years (Japanese to English as it so happens). A good translator is constantly at play with the concepts and meanings that the various words are employed, at times somewhat imperfectly, to get across from mind to mind in given times and contexts. One of the first things it occurs to my translator self to do is to check into the source text and consider what, if anything, might be noticed there that may not occur to a reader of the resulting translation. It is also often helpful to consider the background context of debates in which words were employed.

TMC is a translation of Mises’ 1912 Theorie des Geldes und der Umlaufsmittel. “Commodity money” was the term used to translate Sachgeld. Although some issues have been found with the TMC translation, including most notably the title itself (see the recent centennial symposium volume,The Theory of Money and Fiduciary Media(2013), “commodity money” seems a perfectly reasonable translation in this case. To be clear, I am aware of no reason to think that Mises would have objected, or did object, to this choice. In Nationalökonomie, the 1940 German precursor to Human Action, many instances of Sachgeld are accompanied by the usual examples of gold and silver, which also serve as the stock examples of “commodity money” in Human Action in 1949.

Nevertheless, our purpose is not to toy with words, but to better understand their theoretical content and meaning, and specifically to look for some assistance on the challenge of reconciling Bitcoin with Mises’s original categories. Bitcoin is a novel enough development that it forces us to revisit in a new context of knowledge fundamental concepts that were arranged and labeled as they were in a previous context of knowledge.

In this process, one language might provide hints that another withholds. A word that was unobjectionable in the past might begin to suffer now for the first time from outmoded or non-essential connotations. Moreover, this is likely to occur somewhat more strongly with regard to the particular words and senses of words used in one language than with the corresponding words and senses of words used in another. It is in this spirit that some multilingual brainstorming might lead to a missing clue.

Lt. Cdr. Data sleuthing in Star Trek: The Next Generation.And indeed, the two-part compound construction of the German word Sachgeld suggests some related connotations that “commodity money” in English does not. Die Sache is a “thing,” in either a concrete or abstract sense. Alternative senses from this word and associated compounds readily include such abstract senses as “the matter at hand,” “the facts of the situation,” and “the main or most important point or issue.” A Sachbuch is a non-fiction book (not a “commodity book,” but a book about any non-fictional topic, a “factual book” as opposed to a fictional one). Sachgeld itself in modern dictionaries comes across as any “thing” (or even animal or person) that was historically used as a medium of exchange, or simply the earliest forms that money took historically (note that historically here also implies prior to the evolution of money substitutes).

It appears that Sachgeld, in its first, most literal possible sense, looks like “thing-money” or “fact-money.”

This may already be enough of a clue to begin threading a path through the “commodity” puzzle that Bitcoin, perhaps now for the first time ever, presents. One of our central underlying themes this time will be continuing to seek ways to disentangle the concept of tangibility from various other concepts relevant to monetary theory, especially scarcity. A “thing” is usually considered tangible, but unlike “commodity” in its relevant monetary meaning (a fungible physical material), “thing” more easily also covers abstract senses such as “matters at hand,” “conditions,” and so forth, as in, “The thing is…” or “How are things going?” or “It is a curious thing, this Bitcoin.”

At this stage, rather than creating an alternative category, or turning to a sub-category such as “quasi-commodity money,” it may only be necessary to revisit the original concept of Sachgeld such that it takes on a more abstract and subjective, and less concrete and objective, sense than it has ever been asked to. This would also seem to be in keeping with the overall long-term direction of development of the Austrian school of economics in distinguishing ever more carefully between action-based teleological concepts and objective characteristics of various means employed in acting.

It appears, then, that we might interpret the central economic meaning of Mises’s monetary category of Sachgeld as something like “thing-in-itself money,” or “money in itself,” or “money in fact,” and my re-reading of Chapter 3 of TMC does not appear to exclude this possibility. Much as a silver coin in the old days functioned directly as “money in itself,” and was not “backed by anything,” a bitcoin unit is likewise not “backed by anything.” Nor is it even a perfect or imperfect substitute for anything else. From the point of view of economic actors using it, a bitcoin unit is the tradable good itself. No intermediating substitutes stand between it and its user. And the mere existence of various service providers does not automatically imply that money substitutes are in play.

Paper fiat money is “backed” by such factors as user experience from the past, legal tender laws and user expectations of their continuation, and other powers suppressing certain forms of competition. But Bitcoin enjoys no such force of either habit or law. Moreover, a study of the Bitcoin system suggests no obvious need or function for such money substitutes as have historically grown up around metallic currencies. Not that they are impossible, just that they would not appear to add value. They could even subtract value by adding superfluous risk layers. Many of the advantages that typical money substitutes had in the past, such as freedom from the weight burdens and creeping heterogeneity of precious-metal coins from gradual wear, are already provided in Bitcoin from the point of view of users of “the thing itself” (a topic also addressed in more detail below).

Some knightly context

For an initial check on how well this proposed interpretation might mesh with the greater context in which TMC appeared and its major contributions, we rely on Professor Hülsmann’s definitive intellectual biography, Mises: The Last Knight of Liberalism (2007).

First, we find that Hülsmann noted on p. 215 (emphasis mine) that:

In dealing with the nature of money, Mises relied heavily on the work of Carl Menger. The founder of the Austrian School had shown that money is not to be defined by the physical characteristics of whatever good is used as money; rather, money is characterized by the fact that the good under consideration is (1) a commodity that is (2) used in indirect exchanges, and (3) bought and sold primarily for the purpose of such indirect exchanges.

The words “good” and “commodity” as we read this passage would normally seem to point to physical characteristics, and this was most likely also the intended meaning. But what if we try reading again with abstract senses for these words in mind? The substantive points in this paragraph are all about functional characteristics of money for actors. Look for the verbs: used as, bought, and sold. Moreover, “physical characteristics” are specifically singled out as factors on which money is “not to be defined.”

In quickly reviewing Mises’s typology of monetary objects (pp. 216–217), Hülsmann notes that:

[Mises] distinguished several types of “money in the narrower sense” from several types of “money surrogates” or substitutes. Money in the narrower sense is a good in its own right. In contrast, money substitutes were legal titles to money in the narrower sense. They were typically issued by banks and were redeemable in real money at the counters of the issuing bank.

Here we have the word “good” again. We also have “a good in its own right.” This seems reminiscent of our hyper-literal attempt at rendering Sachgeld as “thing-in-itself money,” or more simply “money in itself.” So far as I am aware, Bitcoin currently has no significant substitutes and virtually no issuers of any such substitutes. Perhaps with a few arcane or experimental exceptions, Bitcoin is so far traded directlyas itself at freely fluctuating rates against all other goods, services, and monies. While the construction of Bitcoin-denominated financial instruments is possible, most all of the actually traded forms of Bitcoin are direct instantiations of bitcoin units.

As Šurda explained (pp. 9–18), Bitcoin is already inherently “form-invariant,” much as language can come in spoken and written forms, but remains language. “Transfer of Balances (ToB)” methods convey Bitcoin units from one wallet to another, while “Transfer of Keys (ToK)” methods, suited for offline use, transfer physically instantiated wallets that contain specified Bitcoin balances (effectively denominations). The private key is physically contained inside a ToK object in the shape of a coin, smart card, etc. with structural and one-time-change physical security features such as holographic coverings and color-change chemistry. Critically, the current wallet balances on ToK objects can be verified if necessary using only the public key without the need to expose the physically concealed private key to any party. None of these ToK objects are Bitcoin substitutes; they are each native forms of Bitcoin itself.

The question of whether actual Bitcoin substitutes and associated practices entailed in the kind of “banking” we are accustomed to could evolve on top of Bitcoin is a separate and open one. Šurda has also just recently offered some further observations on this in an interview with Jon Matonis in American Banker, “How cryptocurrencies could upend Banks’ monetary role” (15 March 2013).

The key issue seems to me that Bitcoin both functions as a money in itself and delivers many of the benefits of historically evolved money substitutes, leaving little demand for them to grow up in relation to Bitcoin, at least in the same old ways. In a provocative take on the question of Bitcoin money substitutes, Pierre Rochard has suggested that this type of development might simply render the ongoing debate about banking reserve practices not so much resolved as obsolete (22 February 2013). People will of course attempt to construct all such familiar instruments, but whether they can add any value relative to native Bitcoin and attract any sustained and significant use remains to be seen.

Mises, in developing his own monetary theory in TMC, was also arguing against the assignment theory of money, which holds that money has no real value of its own to actors, but merely functions as a sort of neutral receipt that facilitates deposits and withdrawals on the “social warehouse” of goods. Money, in this view, is simply a “veil,” functioning as a sort of mere claim ticket exchangeable for other goods, but not a good in itself.

On p. 237, Hülsmann explains that:

Mises’s great achievement in his Theory of Money and Credit was in liberating us from the veil-of-money myth…Mises could even rely on Menger’s theory of cash holdings, which already contained, in nuce, the insight that money is itself an economic good and not just representative of other goods.

Böhm-Bawerk had put it this way in an early-1880s lecture (p. 235):

Money is by its nature a good like any other good; it is merely in greater demand and can circulate more widely than all other commodities. Money is no symbol or pledge; it is not the sign of a good, but bears its value in itself. It is itself really a good.

Hülsmann explains the role of Mises’s strict terminology in countering the prevailing assignment theory of money (p. 237):

To combine these elements into one coherent theory required a radical break with time-honored pillars of monetary economics, in particular, with the classical tradition of presenting money as a mere veil. Mises was fully conscious that this was the key to his theory, which is why, in an introductory chapter of his book [Chapter 3], he engaged in the somewhat tedious exercise of distinguishing various types of money proper (money in the narrower sense) from money substitutes. It was these substitutes in fact that were the sort of tokens or place holders that Wieser and the other champions of the assignment theory tacitly had in mind when they spoke of money…While it is true that the value of a money substitute corresponds exactly to the value of the underlying real good (for example, one ounce of gold), the value of the gold money itself does not correspond to anything; rather it is determined by the same general law of diminishing marginal value that determines the values of all goods.

This greater context clarifies that “money in the narrower sense” is a form of money valued directly without any intermediation of substitutes and without mere veiled representational reference to other goods. Money was not just a placeholder or accounting entry, a claim ticket for other goods. It was one good trading for other goods on the market. Moreover, Sachgeld, “money in itself,” was further differentiated from Mises’s other two monies “in the narrower sense” by not being a debt instrument (credit money) and also not depending on any official legal certification or special legal status (fiat money). The primary distinction of money in the narrower sense among all other goods was its wider relative marketability, as Böhm-Bawerk had explained.

This higher degree of marketability then gives rise to an increased value of money as a hedge against uncertainty. If no uncertainty existed, there would be no need to hold cash balances. As Hoppe explains in “‘The Yield from Money Held’ Reconsidered” (2009), in the real and always uncertain world, we do not know in advance exactly what we will want to buy and when, but we do know with much higher certainty that we will want to buy something sometime. The holding of cash balances can be understood as a forward-looking measure we take in relation to this degree of perceived uncertainty.

No coinbug likes inflation

Whatever the future brings, for today, at least, Bitcoin seems to behave very much like a “money in itself,” but one unlike any the world has ever seen. It is digital and it is apparently impossible for any party to manipulate its total supply. This is critical, because one of the central political-economic monetary issues is inflation, by which I mean specifically, the ability of money producers to manipulate the money supply for whatever reasons they might happen to have in mind or cite at a given time.

As Mises wrote in TMC (p. 428):

It is not just an accident that in our age inflation has become the accepted method of monetary management. Inflation is the fiscal complement of statism and arbitrary government.

He also explained the social-protective advantages of having precious-metal coins circulate physically (p. 450):

Gold must be in the cash holdings of everybody. Everybody must see gold coins changing hands, must be used to having gold coins in his pockets, to receiving gold coins when he cashes his pay check, and to spending gold coins when he buys in a store.

This might seem at first to be the definitive Misesian endorsement of circulating metallic coins. Yet as Hülsmann notes in this context, “Mises had not become a gold bug. He had no fetish about the yellow metal or any other metal” (Last Knight, p. 922). Hülsmann then points us to the reasons behind Mises’s proposal—to help counteract the advance of inflationary policies (TMC, pp. 451–52):

What is needed is to alarm the masses in time. The working man in cashing his pay check should learn that some foul trick has been played upon him. The President, Congress, and the Supreme Court have clearly proved their inability or unwillingness to protect the common man, the voter, from being victimized by inflationary machinations.

The function of securing a sound currency must pass into new hands, into those of the whole nation [world?]…Perpetual vigilance on the part of the citizens can achieve what a thousand laws and dozens of alphabetical bureaus with hordes of employees never have and never will achieve: the preservation of a sound currency.

At this point, much appears to hinge on the definitions of “good” and “commodity.” Must they necessarily maintain their historical associations with tangibility? It is therefore to tangibility, and in particular its relationship with scarcity, that we now turn. Against all the temptations to try to drop Bitcoin into one old basket or another, can Bitcoin nevertheless stubbornly hold out and demand recognition as something new in the world?

[Intermission]

Part II: The Sound of One Bitcoin

That intangible sense of scarcity

In further considering Bitcoin and monetary theory, the concepts of goods, scarcity, and tangibility must be carefully differentiated. Scarcity and tangibility were long inseparable in the form of monetary metals. They remain fused in most familiar goods.

But what if factors other than tangibility, per se, such as relative stability of total supply, durability, and divisibility, were the essential factors even in evolutions of metallic media of exchange? What if tangibility was something of a monetary “inactive ingredient,” a “material carrier” for those other qualities, which had actually always been the essential ones?

Digital goods have brought the separability of goods from tangibility front and center in the modern world. To apply these concepts now to the case of Bitcoin, we revisit their various senses and definitions, including some recent refinements.

Copying is not theft

Most digital goods, such as song or text files can, in principle, be copied ad infinitum even as any earlier copy from which other copies are made remains entirely unchanged.

This was the essence of the digital-information revolution. Unlimited numbers of people could use copies at the same time without direct mutual interference or degradation of the integrity of any earlier copies. A copy could be made without the original disappearing, as would be the case with theft or any other kind of transfer. Moreover, any copy could then become a new, equally serviceable “original” from which new copies were made from there. “Originals” would not even degrade with time or use, as is the case with analog reproduction methods, with their analog “master” copies.

The difference between copying and theft has been humorously and quickly illustrated in the “Copying is not theft” one-minute meme. Since a video may be worth 10,000 words, it might repay the time to view this now to see the essence of this distinction (literally one minute) before proceeding.

The advent of mass digital replication dealt a crushing blow, at least within the abstract realm of knowledge and patterns, to an age-old enemy—inherent or natural scarcity. In response, we have been witnessing a legal and technical scramble to create artificial scarcity to replace it. The major methods have been expanding and tightening legislation and enforcement and the application of digital rights management (DRM) technologies. This combination of developments brought the dusty old issue of “intellectual property” front and center. To make any sense of this odd scene in a principled way required a fresh look at basic social-theory definitions and concepts.

As one important step in this effort, Jeffrey Tucker and Stephan Kinsella in “Goods, scarce and non-scarce” (25 August 2010), focused on distinguishing perfectly copiable goods, such as ideas, methods, and most digital goods, labeling them as “non-scarce goods.” They quoted from Kinsella’s landmark “Against Intellectual Property” (2001), which addresses the relationship between tangibility, scarcity, and the core social function of property rights. Kinsella (p. 19) asked:

What is it about tangible goods that makes them subjects for property rights? Why are tangible goods property? A little reflection will show that it is these goods’ scarcity—the fact that there can be conflict over these goods by multiple human actors. The very possibility of conflict over a resource renders it scarce…the fundamental social and ethical function of property rights is to prevent interpersonal conflict over scarce resources.

This sense of “scarce” is a social-relational one. It refers to the physical impossibility of a rivalrous good being used for different purposes simultaneously by more than one party. For example, one person cannot, under any imaginable scenario, drive from Rome to Vienna while another drives from Sydney to Brisbane in the same car. This specific sense of scarcity derives from the property theory reasoning of Hans-Hermann Hoppe, who wrote in A Theory of Socialism and Capitalism (p. 235) that:

insofar as goods are superabundant (‘free’ goods), no conflict over the use of goods is possible and no action-coordination is needed…To develop the concept of property, it is necessary for goods to be scarce, so that conflicts over the use of these goods can possibly arise.

Care must be taken, as we shall see, because scarcity is sometimes used with a different meaning in economic theory. In that usage, “scarcity” is a necessary attribute of any economic good, by definition. Moreover, in popular colloquial usage, “scarce” has yet a third meaning of “in short supply” or “not enough to go around” relative to an assumed “normal” or ideal baseline situation, which is completely distinct again from either of the two foregoing technical meanings.

Tucker and Kinsella mentioned that tangibility is not inherently necessary for scarcity, citing airspace and radio waves as examples (one transmitter can interfere with another). Yet the practical conclusion seemed to be that tangibility and scarcity do coincide in almost all cases. All of the examples in an informal and illustrative chart of “scarce” goods (and non-goods) happened to also share the attribute of tangibility, while the non-scarce examples were all intangible. And indeed, this is almost always the case. Yet they left no doubt about the key point:

The term scarcity here…means that a condition of contestable control exists for anything that cannot be simultaneously owned: my ownership and control excludes your control.

While the meaning and purpose of their argument is clear in its context, in strictly economic theory terms, one must still act to obtain even a “free” or “non-scarce” copy of a good. One must still click on one free file icon rather than another, for example, displaying choice and preference through this action, and making the clicked-on file a means in action and the runner-up file an opportunity cost. As a result, great care must be taken with the overlapping and sometimes reversed senses of these two meanings of the word scarcity. For example, in the property theory sense, even a “non-good” can be scarce, which is impossible in the economic theory sense. Yet once again, Tucker and Kinsella took care to make their meaning clear:

Something can have zero price and still be scarce: a mud pie, soup with a fly in it, a computer that won’t boot. So long as no one wants these things, they are not economic goods. And yet, in their physical nature, they are scarce because if someone did want them, and they thus became goods, there could be contests over their possession and use. They would have to be allocated by either violence or market exchange based on property rights.

This subtle difference in the meaning of scarcity in economic theory and property theory reflects the respective clarification tasks at hand. Economic theory is in the first instance concerned with the nature of economizing action as such, which can only be taken by individual actors (“Crusoe”). Property theory is first of all concerned with individual action in its capacity as occurring in a social context of other similar actors (Crusoe plus Friday on up). This latter context gives rise to the binary descriptive possibilities of either cooperative (consenting) or conflicting (violent) relationships. One sense of scarcity is used for the purpose of considering Crusoe only, while the other sense of scarcity is used for the purpose of considering the possible classes of interactions between Crusoe and Friday.

Property rights are a fundamentally social phenomenon; they are irrelevant to the consideration of Crusoe alone. And this goes for the narrower sense of the word scarcity used in property-theory reasoning. With Crusoe and Friday situations onward, however, social action theory posits binary action possibilities of either cooperation or violent conflict. These encompass a descriptively possible totality of all possible human interactions (on this, see Murray Rothbard, Man, Economy, and State [MES, 1962] pp. 79–94, and Guido Hülsmann, “The a priori foundation of property economics” (2004)). This particular set of binary classifications has been selected (either more or less consciously) by investigators as being valuable for helping to explain differential social phenomena.

Confusion in discussions of scarcity could also arise from the use of the term “free goods,” which Kinsella and Tucker also associated with non-scarce goods. In the strictly economic theory sense, “free” goods are not really “goods” at all, but the background conditions under which actions take place. They are not means in themselves within an (intentional) structure of action. Rothbard put in this way in MES (p. 8):

The means to satisfy man’s wants are called goods. These goods are all the objects of economizing action…The common distinction between “economic goods” and “free goods” (such as air) is erroneous…air is not a means, but a general condition of human welfare, and is not the object of action.

Air would not be a means for a jogger unless this particular jogger were an obsessive economist who had in mind “using” air as a “means” to go jogging. The air outside under normal circumstances is a background environmental condition, but not itself an object of action, and therefore not a good, unless its supply or quality is threatened. In strict dualist fashion, Mises emphasized how the concept of a means only arises in relation to the study of action (Human Action, pp. 92–93; my emphasis):

Means are not in the given universe; in this universe there exist only things…Parts of the external world become means only through the operation of the human mind and its offshoot, human action…It is human meaning and action which transform them into means.

Means are necessarily always limited, i.e., scarce with regard to the services for which man wants to use them. If this were not the case, there would not be any action with regard to them. Where man is not restrained by the insufficient quantity of things available, there is no need for any action.

Eugen Böhm von Bawerk’s image on 1984 “Austrian” fiat paper. Andrew Jackson sympathizes. Source: Berlin-George, Wikimedia Commons. Good for what?

A “good” is thus something that serves as a means within the structure of human action. Gael J. Campan argues that this was already explained in Eugen Böhm-Bawerk’s 1881 paper, “Whether Legal Rights and Relationships Are Economic Goods.” The first part of Campan’s article “Does Justice Qualify as an Economic Good?” (1999) explains the subjectivist conception of a “good” that Böhm-Bawerk advanced (my emphasis):

While scarcity is commonly referred to as an essential feature of an economic good, this must not be understood purely in a physical sense, i.e., a fewer number of items compared to the quantity of others. Indeed, if all means are scarce by definition, it is specifically because they are limited with respect to the actual ends that they are capable of satisfying…The characteristics of a good are not inherent in things and not a property of things, but merely a relationship between certain things and men.

The thing named a good must have useful properties, which is not to be understood in a strictly physical sense.

As quoted by Campan, p. 24, Böhm-Bawerk wrote (my emphasis; and try it once omitting “corporeal”):

Whatever importance we accord to the corporeal objects of the world of economic goods derives from the importance we attach to the satisfaction of our wants and the attainment of our purposes…It is the renditions of service rather than the goods themselves which, as a matter of principle, constitute the primary basic units of our economic transactions. And it is only from the renditions of service that the goods, secondarily, derive their own significance.

Define “scarce”

We have seen that scarcity in the property-theory sense pertains not to whether something is a good or not in this broader economic-theory sense, but rather to the native potential for rivalrousness of consumption and, specifically, to the presence or absence of the attributes of copiability and simultaneous shareability. Since the broader economic concept of scarcity is already contained within the definition of a “good,” the narrower property-theory sense appears more useful for the current explanatory tasks.

Building on this property-theory sense of scarcity from Hoppe, Kinsella, and Tucker, I propose defining a “non-scarce good” as: a good that is copiable with perfect remainder of the original and useable by multiple actors simultaneously without mutual interference.

Here the two travellers from our previous example, each now with a car of his own, can simultaneously drive to Vienna and Brisbane, respectively, while each listens to identical digital copies of the same album by the same band (each driver incurring his own respective speeding citations). The variable cost of producing each additional playing of this same album is effectively zero (at any rate, quite unlike producing an additional “copy” of a car).

The point for right now is not to enter into the pros and cons of copyright legislation and entertainment business models (on which I recommend work done at C4SIF.org and Techdirt.com), but rather only to show the relevant descriptivedistinctions involved. A copy of a non-scarce good can be freely produced with no objective effect on previous copies, while a “copy” of a scarce good such as a car cannot be made in this way. Either control of the given instance of a car must be transferred (through sale, gift, or theft), or an entirely new instance of a car must be constructed from new and different scarce instances of the requisite materials and energy.

The point of Tucker and Kinsella’s article was to create a relevant binary classification along these lines (my emphasis):

One helpful way to understand this is to classify all goods as either finite and therefore normally scarce or nonfinite and therefore naturally nonscarce…It is scarce goods that serve as means for action, while nonscarce goods that can be copied without displacing the original are not means but guides for action.

…[A] recipe can be shared unto infinity. Once the information in the recipe and the techniques of making it are released, they are free goods, nonscarce goods, or nonfinite goods.

By contrast, according to my suggested definition of a non-scarce good above, the definition of a scarce good (in the property theory sense) would be the negation: a good that is not copiable with perfect remainder of the original and is not useable by multiple actors simultaneously without mutual interference. This proposed definition encompasses what most people think of colloquially as “goods” in general: groceries, clothes, and so forth.

In the modern age, such “non-scarce goods” have proliferated. As Tucker and Kinsella put it, “The range and importance of non-scarce goods has been vastly expanded by the existence of digital goods.” For the most part, non-scarce goods include all sorts of abstract goods such as ideas, text and music files, patterns, plans, recipes, methods, and so on. Specifically, it includes the meaning and content of all types of media and text, and other abstract and digital “things.”

Except…

In the case of Bitcoin, matters are different. Each bitcoin unit can exist in only one wallet at one time due to the Bitcoin protocol’s methods of ubiquitously recording transactions and preventing double-spending. It is critical to understand that these qualities of Bitcoin scarcity are not merely due to add-on “security measures.” They are not appended legal or technical “protections.” Rather they are integraland inseparable attributes of a system protocol of which a given bitcoin unit is one element.

As should be clear by now, it is not necessary to fuss over objectivistic considerations such as whether an abstract collection of digits in certain configurations can “really” be a “good” or not. Böhm-Bawerk’s insertion of the word “corporeality” into his 1881 sentence is not a separate criterion for something to serve as a means, a point we can much more easily see today than over 130 years ago. Böhm-Bawerk nevertheless clearly explained that one must observe what people are doing to understand what economic goods are, an insight that Mises would later take up and run with in his action-based reconstruction of economic theory.

Bitcoin has now brought authenticscarcity into the world of digital goods.

This is not the artificially imposed, legally constructed “scarcity” of “intellectual property” legislation, which was the target of Tucker and Kinsella’s important work. It is not even a type of tacked-on DRM system that attempts to use technical measures to create artificial scarcity out of informational objects that are in their nature not otherwise scarce. The Bitcoin system has set up a type of scarcity that is inherent to the nature of the good itself. This possibly unique achievement of an inherent scarcity within the digital realm is an essential part of the innovation that has made Bitcoin a new type of good.

A bitcoin unit viewed as an object of action also meets another essential criterion from Böhm-Bawerk—it can be controlled. As Campan explained (p. 24):

It is necessary that the thing in question be disposable or available to us. We must possess the full power of disposal over it if we are really to command its power to satisfy our wants…the possession of a good cannot simply be decreed: either you possess effective control over it or not.

The Bitcoin system achieves this through private key/public key encryption, which allows effective control of bitcoin units in a user’s wallet, provided said user maintains control of their private key and/or related passwords. Once a bitcoin unit is transferred from one wallet to another, it is no longer “in” the originating wallet, but only “in” the destination wallet.

Thus, in the property-theory sense of scarcity, a bitcoin unit qualifies, not as non-scarce like most other abstract or digital objects, but as scarce, since according to our proposed definition, it is “a good that is not copiable with perfect remainder of the original and is not useable by multiple actors simultaneously without mutual interference.”

Once a private key to a Bitcoin wallet is copied, more than one party can have the key at the same time, as with any other non-scarce good. However, even so, only one party can succeed in using this private key to make use of any given bitcoin unit associated with that wallet. Only one transaction with a given bitcoin unit can be confirmed in the block chain. Even though a private key or password can easily be copied if obtained, even in this case, only one person can end up succeeding in making use of a given bitcoin unit because of the system’s prevention of double-spending. A known compromised key pair (wallet) can be abandoned. Additional key pairs are free and plentiful.

What is the sound of one bitcoin?

Two hands clapping make a sound. What is the sound of one hand?

—Koan attributed to Zen Master Hakuin Ekaku 白隠 慧鶴 (1686–1768)

We have seen that the concept of scarcity in both economic-theory and property-theory senses is useful to understanding bitcoin units as objects of human action and that scarcity and tangibility are separable. But can the quality of tangibility, so essential to the familiar story of the evolution of precious metals as monies, just be unceremoniously dropped? It is said that an experienced examiner can distinguish the authenticity of a precious metal coin by dropping it and listening to its ring. But what is the sound of a bitcoin dropping?

It was tangibility in the monetary-evolution story that had seemingly held together all the numerous traditional monetary-commodity characteristics in the form of a nice solid coin of silver, gold, or copper. It appears that some observers steeped in that story, upon seeing that Bitcoin lacks tangibility, concluded that it must also lack the other associated monetary characteristics such as durability and relative stability of supply.

In this context, we find it insightful that Jon Matonis, a long-time observer of and writer on cryptocurrenices, recently said in a Reddit interview (19 March 2013) that one way to quickly understand Bitcoin better is that it is distinguished from gold in that “it depends on mathematical properties rather than chemical properties.”

A “hard-money” checklist check

With these considerations in mind, this paragraph from Professor Hülsmann from “How to Use Methodological Individualism” (27 July 2009) will be helpful. The essay was on a different theme, but the following paragraph from it contains a great deal of interest for our current topic all in one convenient place (my emphasis):

Media of exchange become ever more generally accepted to the extent that they are objectively more suitable than their competitors in arranging indirect exchanges. Silver is more suitable as a medium of exchange than cherry cakes because it is durable, divisible, malleable, homogeneous, and carries a great purchasing power per weight unit. Market participants are likely to recognize this relative superiority in a process of learning and imitation, and eventually most of them will use silver to carry out their transactions. Hence, one can explain why the technique of indirect exchange is adopted on an individual level; and one can explain why specific media of exchange become generally accepted and thus gradually turn into money.

There is much of relevance in that paragraph, but for now, I will only consider how bitcoins seem to fare against silver coins on those very characteristics (plus stock stability) on which silver coins beat cherry cakes:

Divisible, malleable, and scarce. Source: Mikela, Wikimedia Commons. Are bitcoin units…

- Durable?Perfectly. Abstract digital objects do not change. However, this is subject to recording and replication, substrate non-destruction, private keys and passwords not being lost, etc.

- Divisible?Current theoretical maximum of 2.1 x 1015 units to be reached around 2140, with future extensions apparently also possible (finally enough tradable units for the “needs of trade”?).

- Malleable? Irrelevant; not tangible. However, analogs of this quality may be found in the variety of “transfer of keys” code-recording methods such as hologram- and color-change-protected code-bearing physical coins and cards.

- Homogeneous? Perfectly. More homogeneous than possible with any conceivable physical material because the homogeneity is mathematical (by definition) rather than physical (by empirical measurement relative to a definition).

- Purchasing power per weight? Infinite. Intangible code patterns lack the characteristic of weight altogether, rendering the slightest purchasing power infinite in per-weight terms.

- Now add: Relative stability of supply? Quantitative growth and terminal maximum quantity and timing are determined computationally; macro supply of bitcoin units (theoretically) not subject to human manipulation.

On this initial reading, it appears that Bitcoin obliterates metallic coins on factors 2–5, whereas factors 1 and 6 are open to contingencies and informed technical debates. Just as silver coins beat cherry cakes on these criteria (except malleability!), Bitcoin beats silver coins outright on four of six criteria. The other two criteria require further investigation, but Bitcoin also appears potentially competitive and possibly superior on these characteristics as well. These are questions for empirical observation, debate, prediction, and speculation about the specific course of the future, not for abstract theory as such.

This analysis of Bitcoin suggests several other points with regard to several of these characteristics.

First, purchasing power per weight was a major impetus in the evolution of paper and account entry substitutes for precious metal coin monies. Bitcoin’s purchasing power per weight is already infinite, and is therefore, quite literally, unbeatable on this factor. Another problem with metallic coins was gradual wear from circulation, which would eventually give rise to weight variations—a loss of homogeneity resulting from imperfect durability. Bitcoin does not share these particular defects with metallic coins that helped lead to market demand for substitutes.

Second, people tend to interpret the traditional hard-money characteristic of durability as a mainly material one. Tires, for example, are described as being more or less durable. On reflection, however, a temporal aspect is central to the concept of durability in that it refers to measurement of change over time in relation to use. To ask about durability is to ask the extent to which an object tends to change over time in certain of its properties under certain conditions. In the case of an abstract code relationship, the code need not change at all. Although its recording substrates might change, the code itself can be perfectly copied and copied again, and it is in this specific sense that its durability as a code sequence is theoretically infinite for any relevant purpose.

Third, regarding divisibility, whereas fiat money issuers stand ready to add as many integers (“zeroes”) to paper fiat notes as they like to facilitate the steady loss of value of fiat monetary units; the Bitcoin system is capable of supporting divisibility to as many decimal places as are demanded to facilitate a steady gain of value over time. This is a diametric contrast the further implications of which would be difficult to overstate.

Competing ways to approximate a golden spiral. Source: Silverhammermba, Wikimedia Commons. Comparative versus imaginary-perfection methods

The ultimate potential for manipulation of the total Bitcoin stock (factor 6 above) is a key question that is certainly a very technical one, possibly with philosophical aspects. Can it be established that future quantitative supply manipulation at the macro level cannot occur? Would that require “proving” a technical and empirical negative?

Whatever the factors and answers, it is important to apply the realistic comparative perspective of the true economist rather than the “imaginary-perfections” perspective of the false one. For example, with fiat monies, we know above all that large-scale, distortive, quantitative manipulation of the money supply can occur—andin all known cases actually does.

Even with metallic currencies, comparisons on hypotheticals would still have to be even-handed. The stock of precious metals adjusts slightly over time with mine output and other factors (though always with much less volatility than the stock of a fiat money). Nevertheless, at the extreme, can it be shown that cheap synthetic gold could not ever be produced (as the alchemists had forever dreamed), thereby collapsing the price of gold by inflating its supply? (as the alchemists may or may not have thought through far enough).

Gold can apparently already be synthesized in particle accelerators and nuclear reactors, just not cheaply. If one of the criteria required of a candidate for becoming a sound money is proof of a fantastically complex technical and empirical negative, then such must be required equally of all potential candidates. If, for example, it must be “proven” that no mass quantitative manipulation of Bitcoin could ever possibly take place under any imaginable conditions, then it must likewise be “proven” that no future cheap gold synthesis could ever possibly take place.

Empirical perfection never comes to pass. In all such matters, the comparative method must be recalled and put to use. Pros and cons of possible alternatives must be assessed. Critical comparisons against made-up and wholly unrealizable hypothetical states of empirical perfection must be identified and rejected.

Unfortunately, just such clouded thinking has been ingrained and normalized through the practice of assuming that state actors can successfully and perfectly accomplish whatever they like by enacting legislation and setting up a bureaucracy. This patently absurd dream is then compared (at best) to the forever imperfect efforts of the living human beings who by contrast inhabit the so-called “market” (which euphemistically seems to mean “reality”).

Human action is by nature always a choice among perceived possibilities. The Misesian tradition of economics is positioned as one part of the study of human action. The study of society is the study of acting persons joined in a grand, interacting process of trial and error writ large.

It is not the role of economic or legal theory to predict the future. However, they can and do have useful and unique contributions to make to basic understanding. These can in turn prove useful in such other fields as investing, forecasting, and business-model development that do attempt the always-speculative and risk-bearing task of peering ahead into the soon-to-become empirical future.