The German word Nachklang denotes what resonates after a sound has passed. It is the tune that still plays in one’s head after external sounds have faded. I have been listening to what stays with me in the few days after attending the Bitcoin Europe conference in Amsterdam September 26–28, prior to setting out toward the Crypto-Currency Conference in Atlanta, October 4–5.

Many conferences have a “keynote address.” I think Bitcoin Europe had more of a keynote moment on the final day that reflected the heart of the whole affair. This came when Bitcoin Magazine editor and software developer Mihai Alisie punctuated his moving presentation with, “Bitcoin is here to serve humanity, not to rule it.”

Now that resonates.

Takeaway themes included 1) the need to keep developing more intuitive client software, 2) the desperate need to help improve the global remittance market, which Bitcoin is technically capable of revolutionizing rather quickly, and 3) the need to implement multiple-signature transactions in client software. While that last item may seem obscure, we will return below to its potentially immense long-term implications.

The conference was heavy on entrepreneurs and programmers, often combined into the same persons. Bitcoinj developer and smart contracts enthusiast Mike Hearn could usually be spotted in the lobby talking with someone while looking over a screenful of code on his laptop. Massive effort, energy, and ingenuity is in play, with untold separate projects underway. One person after another I talked to, or who was presenting, was working on some project to develop new wallets, improve existing wallets, develop new exchanges, develop new ways to do exchanging, offer new ways to do remittances and loans, incubate startups, and generally make payments easier and more accessible and secure for wider audiences. That most definitely includes all those underserved, mis-served, or not served at all by the world’s existing constellation of financial institutions.

The tragedy of international remittances

A key concept was that Bitcoin is likely to start meeting needs and expanding most quickly right where existing “points of pain” are most intense. Sure, Bitcoin is better for online payments than credit cards in almost every way, but the epitome of a global point of pain is international remittances.

Immigrants working in wealthier countries trying to send some of their hard-earned wealth back home to relatives in poorer countries face truly dismal options. For every dollar, euro, or yen earned, some portion ends up making its way back home, but conventional remittance services charge shockingly high fees, trimming large percentages off of the fruits of labors undertaken mainly for families elsewhere.

One could call this a scandal, but the scandal is not so much the practices of the visible companies that do manage to provide this service at all, but the Byzantine regulatory mesh behind the scenes that makes it so difficult to do so efficiently. This regulatory overgrowth chokes off this market to the authentically open competition that could lead to lower costs and improved services rather quickly.

Into this fray, Bitcoin technically already enables international remittances with basically no charge for those few (for now) who are able to use it directly at both ends. “Send value anywhere in the world instantly in any amount and essentially for free” is a bold claim. No company can make it, but the decentralized Bitcoin network can and does deliver on it already.

Still, companies still have many roles yet to fill by leveraging the Bitcoin network and connecting people to it in ways they are not yet able to do for themselves. For almost all those who want to do international remittances today, some additional services are required. A remittance provider leveraging Bitcoin in the back office for transfers, while providing cash or local bank integration at one or both ends could offer the same or better service as Western Union’s or MoneyGram’s current offerings at vastly lower fees.

End users need not even necessarily know anything about Bitcoin or realize that it is involved in aspects of international transfers between local offices. They only need recognize that a much higher percentage of their purchasing power actually makes it back home, faster.

To illustrate, Daumantas Dvilinskas, CEO of TransferGo, based in Lithuania, talked about how his company is working to provide faster and less expensive international transfers. He quipped, “It takes three days to send money from the UK to Lithuania. People went to the moon in three days.” I live-tweeted this and Twitter user Jacob Norup Pedersen added, “it takes two weeks from Denmark to Morocco.”

The ecosystem metaphor

In reflecting on the sheer number of business ideas and variations being developed—even just those visible at this conference—I had the image of an exploding Cambrian ecosystem with a large number of candidates for longer-term survival. Many seem promising. In the end, only a few will multiply and advance toward wider adoption. Knowing which ones will be which is an extraordinary challenge. Complicating this further, the “DNA” from one project can easily hop to another in this primordial open-source soup, remixing again and again until successful combinations are found and then built on further. An abundance of candidate code segments and strategies is right there in the open to be borrowed. It is only the process of doing, trying, and offering that will end up delivering the many new conveniences that even today’s skeptics will most likely be taking for granted in daily life in the near future.

BitPay CEO Toni Gallippi, whom I met for the first time on the last day, was on hand representing what a wildly successful Bitcoin business can already look like, having gone from a thousand merchant accounts to 10,000 in the past year. Not coincidentally, his presentation and informal comments off-stage were positive and constructive and showed how his company makes life easier for both merchants and buyers compared to conventional payment options.

This goes right down to the details. Even the Bitcoin to fiat-money exchange rate that pops up when a customer pays a merchant through BitPay is likely to be more favorable than the rate they would get by selling Bitcoin on an exchange for cash. This is due to the company’s use of a custom bid and ask book that integrates live data from across the major exchanges.[1]

Regulation is a much broader social problem

The conference was a microcosm of the true market spirit. On balance, this crowd seemed to view existing regulatory structures—always beloved of industry incumbents as a way to protect themselves against disruptive start-ups at the general expense of consumers—as fairly pointless obstacles, unfavorable environmental features that would-be surviving organisms must simply be able to deal with.

Bitcoin core developer Jeff Garzik, who joined the “Borderless Solutions” panel on the final day, commented that Bitcoin just is a borderless solution by nature. The only need for “borderless solutions” per se, is for particular Bitcoin-related entrepreneurs to try to function amid the various and mixed obstacles left in place by legacy nation-state barriers.

Still, the official presence at the conference went a long way toward confirming an impression I have had for some time. Most governmental officials around the world want to figure out how to perform their various jobs, which mostly consist of applying existing legislation and administrative codes to rapidly evolving market phenomena. They are not generally out to make up additional onerous regulations just for the sake of being troublesome.

There is no need for them to do so. This is because shelves of thick volumes of legislation, administrative code, and case interpretation are already available to guide the obstruction of hapless innovators. Such things already exist and are not being conjured up anew just to harass Bitcoin enthusiasts. Ambiguity about which regulations are to apply in particular cases is also already part of the structural problematic of the legislative law approach itself. Whether this approach is just or helpful to society is a much larger topic (hint: I think it is clearly neither just nor helpful to society). Bitcoin just provides some fresh (and perhaps embarrassing) contrasts with existing systems and practices that work especially poorly.

Wieske Ebben, from the Dutch central bank, joined the panel on regulation. She (being among the approximately 2% of conference attendees who were female) clarified several times that one of the bank’s central concerns in its role as national financial regulator is to make sure new payment systems are trustworthy in the interest of consumers.

Although somewhat at the expense of Ms. Ebben, who seemed a little taken aback, Berlin’s iconic Bitcoin-kiez promoter Jörg Platzer drew a round of applause with a comment made from the seat next to her on the panel. He pointed out that word on the street has it that the public does not now consider central banks and large commercial banks themselves as icons and worthy arbiters of trustworthiness in society.

Yet this understandable focus on assuring trustworthiness is potentially quite a positive sign in light of the reality of Bitcoin (as opposed to the typical media hype). As Toni Gallippi pointed out later, many Bitcoin users believe it is among the most trustworthy and secure payment systems ever devised.

First of all, Bitcoin is immune to certain inherent weaknesses in credit cards that give rise to massive ongoing fraud and identity theft (even after decades of expensive efforts to combat such problems). A Bitcoin payment is pushed by the user, not pulled by the receiver using sensitive information. Receiver-pull methods require the transmission of sensitive financial data, making such data vulnerable to interception or hacking right out of company databases. With Bitcoin, only a cryptographically signed transaction is sent, and, unlike with credit cards, this contains no data that can be used to create additional fraudulent transactions later. With Bitcoin, identity theft cannot be used as a basis for spending other people’s money.

Moreover, Bitcoin cannot be counterfeited, a problem that continues to plague physical cash, despite a centuries-long technical battle between official money printers and counterfeit money printers, a battle that has led up to the most advanced modern papers, inks, plates, and embedded features on one side—and ongoing successful counterfeiting on the other. And as for the real traditionalists, it should be noted that metallic coins and bars, especially gold ones, were ever plagued by reductions and dilutions to weight or purity from both criminals and kings. In contrast, Bitcoin cannot be clipped, sweated, embedded with tungsten, or mixed with just a tad more copper or silver with each new minting.

Niels Ploeger, from the Amsterdam police department, was also on the regulatory panel and attended much of the rest of the conference as well. He explained that he was tasked with researching and better understanding Bitcoin to provide insights that could be useful in informing criminal investigation procedures.

One key point for investigators is that Bitcoin leaves a permanent and unforgeable record of all transactions, with amounts, accounts and time stamps down to the second. This should, in principle, be much more useful and easier to track than cash in the course of specific criminal investigations. Each bitcoin unit has a permanent, public trail behind it. Even if it does go through a mixing service at some point, this fact too can be surmised to some degree, along with the timing of the mixing.

It is true that particular addresses are not directly linked to particular human or organizational identities within the Bitcoin block chain. This is a critical feature, as the presence of such linkages on a public ledger would obviously eliminate the possibility of any user privacy for anyone for any purpose (btw, destroying all privacy is ever the dream of totalitarians).

Still, for those legitimately investigating specific crimes, block chain clues combined with other evidence can lead investigators to insights unavailable from cash. In addition, conventional banking and accounting systems, despite untold piles of regulatory paperwork, should also not simply be assumed to be immune from all manner of forgeries, frauds, and misrepresentations. Comparing one real system against the imagined perfections sometimes tacitly assumed of incumbent systems should be studiously avoided.

A point raised at another time during the conference was that for Bitcoin to succeed in an enterprise context, it will be important for organizations to be able to keep sensitive information private (for example, from competitors) and to make other information publicly verifiable (raising confidence that, for example, reserves or bonding funds are actually present in a specified account). This means that the entire range of user-defined privacy options Bitcoin offers, from 1) high anonymity (possible but somewhat difficult to actually achieve in practice) to 2) pseudonymity (traceable with some specific investigative effort; the most common case) to 3) globally public auditability (for charities or public agencies, for example), are all important, just in different applications.

A quick interlude on privacy, anonymity, and today’s DPR arrest

Just as I was about to finalize this essay, the arrest of Silk Road operator Dread Pirate Roberts was announced. While the complaint seems generally reasonable-looking in terms of the chain of evidence presented, it repeats the usual dubious claim that Bitcoin “was designed to be anonymous.” It was actually designed, which is a matter of public record, to enable people to transact securely, relatively free of fraud or censorship, at any distance, and without the need to rely on (and pay) third parties that may or may not be trustworthy (see Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System (2008) by Sataoshi Nakamoto).

It should be noted that assessment of the complaint’s merits on its own terms, which must, given its nature as a positive law document, tacitly assume that the existing state of laws is as it should be, must be separated from normative views on the logic or net value of drug criminalization. For example, relevant to such assessment would be evidence that prohibition laws have a dramatic, consistent, and well-documented role in increasing violence in society, including precisely that sort of blackmail and retaliatory violence also alluded to in the complaint, violence that is typical of the operations of any market that is forced underground, such as the gang activity during alcohol prohibition in an earlier phase of US history.

Despite repeating the usual false claim that Bitcoin is inherently anonymous, the complaint then surprisingly goes into several details, each of which contradicts this claim. It discusses the public nature of the block chain and cites detailed sales data obtained from examining specific addresses. It then explains all the additional measures that the site’s operator put into place—beyond simply specifying Bitcoin as a payment method—to try to make the transactions anonymous (which they already would have been to begin with if the misleading claim of inherent anonymity were true). In the event, the arrest was made largely on non-monetary lines of evidence, specifically items such as server trails and linkages among user names.

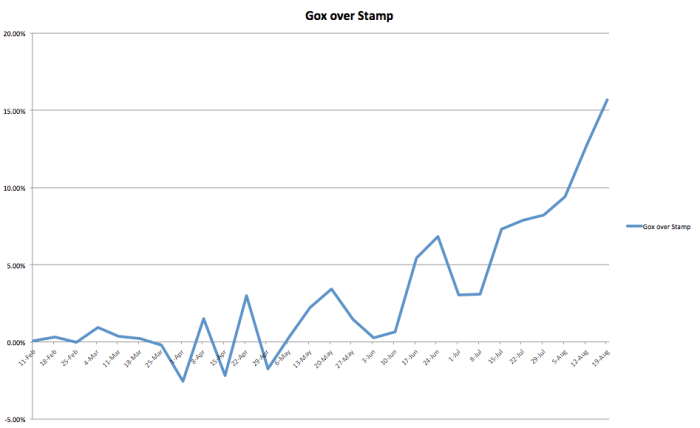

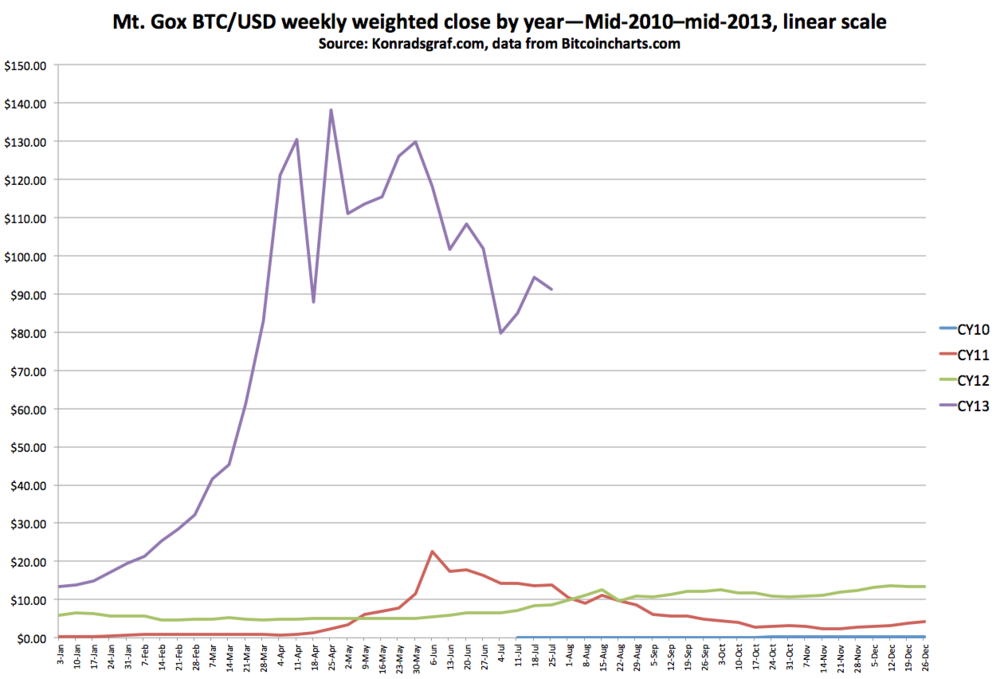

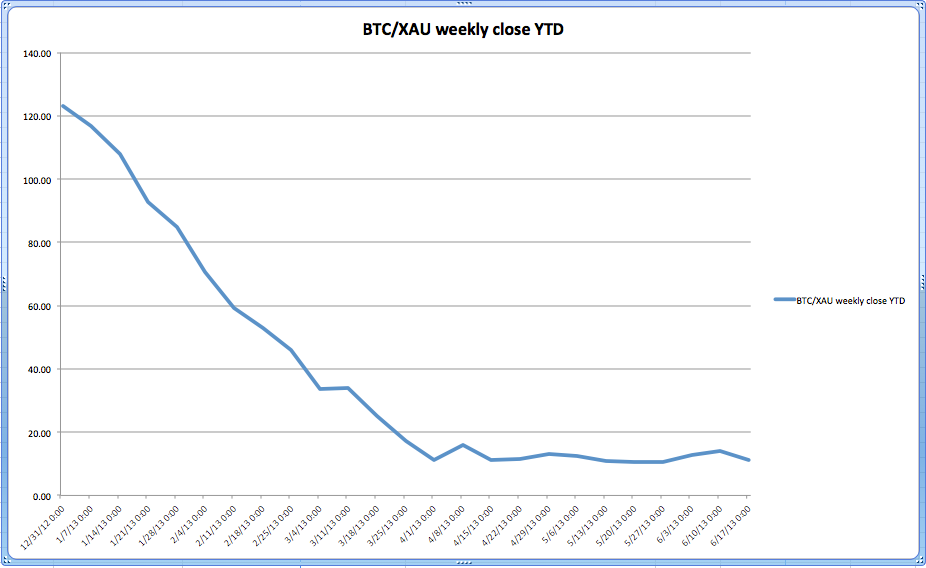

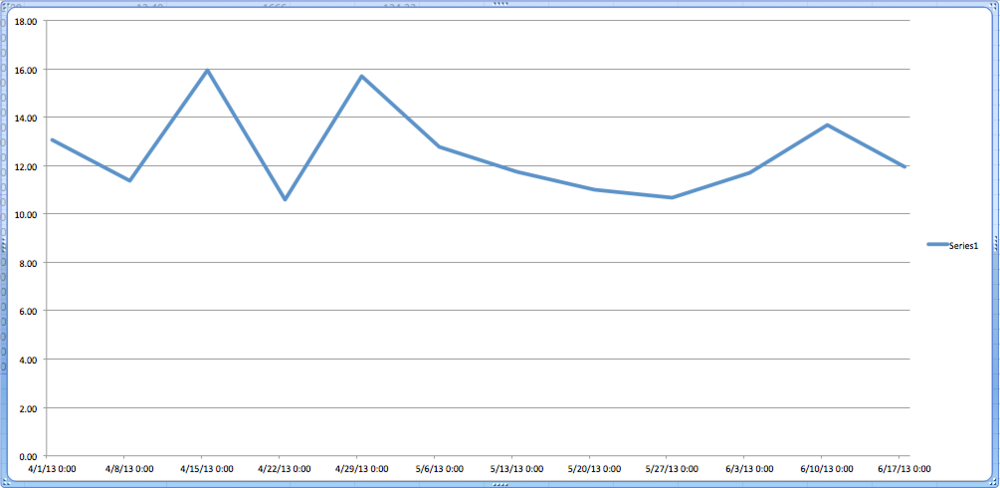

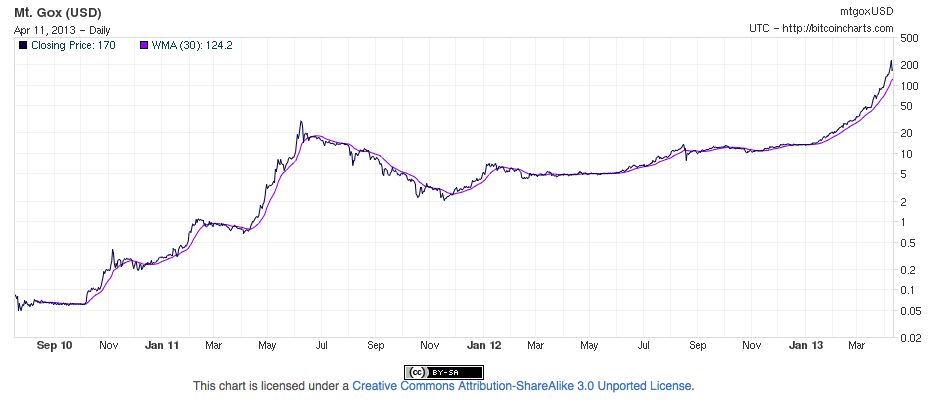

With all the repeated media-hype that the “main use” of Bitcoin is for illicit purchases (also a highly dubious and factually unsupported claim), it should be interesting to see how much the exchange value of Bitcoin reacts over the coming weeks and months—beyond the obvious short-term panic selling followed by opportunistic buying on the dip—to the shut down of the oft-referenced black marketplace.

To serve and to secure

The overwhelming spirit I sensed at the Bitcoin Europe conference was one of service to those who can benefit from these innovations next. Now that the relevant classes of geeks and early entrepreneurs get it, how can these new possibilities be brought rapidly to everyone else, starting with some of those who could benefit most?

While several speakers reiterated the lingering difficulties of “mom and dad” or “grandma” understanding and using Bitcoin, Willem van Rooyen of SC2BTC, who is working to integrate Bitcoin into eSports (high-skill online gaming matches as spectator entertainment), reported that his target customer demographic has no difficulty at all understanding and starting to use Bitcoin with existing solutions.

Yet the question remains: How can services be made that are easier for more people to benefit from and that will be more resilient and secure with minimal reliance on user savvy?

In this spirit, early entrepreneurs are working, each from slightly different angles, to bring the current and potential benefits of Bitcoin to more and more users around the world. They will do this no matter what obstacles may or may not be placed in their paths, because this is their dream, their vision, their mission, and their rightful role.

Bitcoin as foundation layer for new possibilities

I noticed a strong confluence between my most recent reading and some of the services and technologies featured at the conference. I have been researching and thinking about legal and economic theory and how they relate for some 25 years. It was in this context that I first began to take note of Bitcoin in mid-February of this year. Since then, I have been learning the essentials of the relevant principles in computer science and cryptography as fast as possible in order to make sense of Bitcoin by combining social theory and technical theory in appropriate ways. When it comes to Bitcoin, taking a strongly multi-disciplinary approach is not optional.

Bitcoin was a major breakthrough in the advancement of several much broader sets of ideas. It has created an infrastructure layer that can now greatly facilitate further developments based on those feed-in concepts. These include smart contracts, triple-entry bookkeeping, and additional applications for decentralized unforgeable ledgers such as securely recording titles to other kinds of property.

Michael Goldstein got me started recently going back and reading key works by Nick Szabo that substantially predate Bitcoin, but also contributed greatly to the intellectual milieu out of which it emerged. Michael, along with Daniel Krawisz, will be going into these concepts on October 5 in Atlanta on the “Cryptography and Contracts” panel, and I am greatly looking forward to hearing and discussing more.

As it was, next up in my queue prior to Bitcoin Europe was the seminal article, “Formalizing and Securing Relationships on Public Networks” (1997), which I assigned myself for the relevant flights. At the conference, then, it was striking when several different developers pleaded on stage for more end-user wallet software makers to add support for multi-signature transactions. The convergence is that it is just such transactions, already supported in the Bitcoin protocol, that can make possible not only increased layers of security, but also the next evolutions in smart contracting, including escrow and assurance contracts and the likes of decentralized peer-to-peer loans and verifiable-balance safe-keeping services.

Bitcoin’s functions as information-age payment method and unit of trade may only be the beginning. Deep transformations may also come in the fundamental ways that contracts and agreements come to be implemented, recorded, and performed.

As Szabo showed, the first phases of taking traditional accounting, fiscal controls, and contracting into the digital world mostly just copied traditional paper systems and digitized and networked them. That change had both advantages (speed and accuracy) and disadvantages (privacy and security) compared to the original paper-based systems. However, new technologies could also lead to new methods that were not possible at all on paper, but are enabled for the first time ever by advances in cryptography and related developments.

To get a better image for this distinction, imagine that when powered flight was first developed, pilots had only flown routes right above existing roads. This is better and faster than surface travel, but still not great. It is only when they start to do something that only the new technology allows at all—flying straight from point A to point B, that the more interesting possibilities actually begin to emerge.

Computerized accounting has, in this view, been using the new airplane simply to move much more quickly along above the same old surface routes. In contrast, brand new options built on decentralized financial cryptography, unforgeable hashed transaction chains, triple-entry accounting, and multi-signature and other smart contracting modalities—bigger idea sets that predated and contributed to the invention of Bitcoin—look a lot more like the beginnings of leaving the old surface routes and starting to fly as birds do.

The role of social theorists

It was a pleasure at this conference to finally meet Peter Šurda, a long-time Bitcoin researcher also influenced by the Austrian school approach to economics that began taking its modern forms at the University of Vienna in the 1870s. When I started researching Bitcoin, his was among the first names that began rising toward the top of the discussion forum soup as I began to think about the monetary nature of Bitcoin. He quickly made it into my initial “knows what he is talking about” short-list. Even better, it was a bit of a relief and encouragement to me working in early March to notice that he had independently arrived at some interpretations of the relationship between Bitcoin and traditional monetary classifications that were quite similar to the ones I was initially entertaining.

Peter also told a story about our meeting in his quick post of highlights from the conference. One of my favorite short books on monetary theory is The Ethics of Money Production (2008) by Jörg Guido Hülsmann. When I asked Peter if he had read it, he said, “yes, twice.” I laughed and said that I had also read it twice. What an unusual moment! The global population of people who have done this and attended a Bitcoin conference must still be rather small indeed.[2]

Another time, Peter and I were (half) joking about the proper role of economists in the cryptocurrency revolution. He said the first response of many economists to Bitcoin seems to be denial: Bitcoin is not real and it will fail shortly, just like other hair-brained funny-money schemes throughout history. We have seen plenty of that denial phase, mainly from people who do not seem to have investigated the technology all that much.

My informal empirical generalization is that knowledge of Bitcoin and fascination with or enthusiasm about Bitcoin tend to correlate strongly, as do technical ignorance of the subject and easy categorical dismissal. Notice that we expect matters to be exactly opposite to this when it comes to unsound schemes. In such cases, the more one investigates, the less there is to like, whereas most of the enthusiasts seem to have been swayed by hyped surface appearances, and may even be unwilling to actually look more deeply.

Opposite to denial, the main role of economists, and legal and other social theorists more generally, should be to carefully observe what is happening in the real world and seek to provide systematic theoretical interpretations. It is the entrepreneurs who rule (in service of consumers, who really rule through their buying choices). It is the economists who should be running along either behind or at best next to these real actors and trying to figure out what is happening in a theoretical or more systematic way, adding some insights when and if they can.

This is especially so when an economy is in the midst of an epoch-scale revolution (as in agricultural, industrial, informational). The Spanish late scholastics, observing economic transformations in trade and money, became among the first to start writing insightfully about specifically economic-theory and monetary-theory concepts some 500 years ago. Later, first-hand observers of, and participants in, the industrial revolution—most famously Smith, and more promisingly Say, Turgot, Bastiat, and others—began to make further advances (or sometimes regresses, but still) on top of their observations of new developments.

Economists do have their rightful places. This was evident during the conference, thankfully only a few times, when specialists in other fields edged over into the proper territory of economic theory and the average quality of their causal claims then declined precipitously compared to when they were discussing, say, business, contemporary positive law, or software. This is not a call to leave everything to specialists, but a call for everyone to take steps to advance and improve their own literacy in real economics. As Ludwig von Mises wrote near the end of his landmark Human Action: A Treatise on Economics ([1949] 1998, 875):

Economics cannot remain an esoteric branch of knowledge accessible only to small groups of scholars and specialists. Economics deals with society’s fundamental problems; it concerns everyone and belongs to all. It is the main and proper study of every citizen.

Let theorists theorize and doers do

The world is upside-down to the extent that so-called economists occupy positions of administrative power and influence over their fellows to “guide economies,” a euphemism for micromanaging and telling entrepreneurs and consumers what to do and what not to do. The result is the mixed(-up) economy world we inhabit, a world that is perhaps most mixed up of all when it comes to conventional financial systems.

The world becomes reoriented when economists are positioned as observers and theoreticians, helping people understand how it is that the uniquely human capabilities of voluntary social cooperation and mutual service make society possible. Economists can help clarify the puzzle of the world in unique ways. They should observe and bring clarity to what is otherwise a mysterious chaos of real-world progress as it unfolds at the hands of consumers, investors, and entrepreneurs. Economics is supposed to be a science, not a presumptive license to micromanage and direct those who are busy doing the actual work.

For those who do chose to specialize in economics and other aspects of social theory, today offers some amazing opportunities to occupy front-row seats to epoch-scale transformations of the technologies of market exchange. Previous epochal economic revolutions happened over centuries and decades, recognizable mostly only in retrospect. This one appears to be happening over a few years, with increments measured in months, weeks, and even days.

At Bitcoin Europe, the entrepreneurs and developers were the stars. This is the world as it should be. In roles as theorists, a few of us were observing in awe, wonder, and curiosity, following a major social evolution live as it unfolds. In that particular role (playing other roles in addition might double as good research), we operate first from curiosity—to understand for ourselves—and only then to see if we can help make it easier for others to do the same.

Atlanta promises to offer a slightly different mix, still with discussions of entrepreneurship and concrete innovations, but with a little more direct material on economic and contract theory in addition. Some of the original visions that helped give rise to Bitcoin have much more unrealized promise to bring for the benefit of us all.

For all the signs put up in gloomy dismay at the course of the conventional financial world, which effectively say, “the end is near,” we who track promising new innovations need to keep putting up other signs, in different places, that add a counterpoint: “the beginning is here.”

[1] For a recent theoretical discussion on the respective roles of unit of pricing and medium of payment, see my 14 September 2013 article: “Bitcoin as medium of exchange now and unit of account later: The inverse of Koning’s medieval coins.”

[2] For those interested, my article, “The sound of one Bitcoin: Tangibility, scarcity, and a ‘hard-money’ checklist” (19 March 2013), makes a step-by-step theoretical case as to why a hard-money position is fully compatible with a strange new currency that has no physical existence! If that seems impossibly counter-intuitive, you might understand why I spent about 9,000 words taking an initial shot at doing this. I have made a few refinements since then, not yet published, but the fundamentals remain the same.